Share

I’ve just read a couple of articles about why products fail in the marketplace. For a product manager like myself, this is both interesting and scary! It’s the kind of thing that can give you sleepless nights. Product failure rate has remained high and constant over the years; some estimates place it at about 85% for consumer goods. So why is that?

One article I read explained that, although product managers are often very experienced, and have marketing research information about the new products—often of good quality—the issue is that they "want" the product to succeed. Managers are not so much failing to understand customer needs as failing to see just how many customers have this need. Are they addressing a niche—and how big is it, compared to the overall market?

The other article featured a list of potential reasons for new product failure such as incorrect pricing, poor execution or late entry to the market. However: top of the list, and a key feature of the first article too, was failure to understand the customer’s wants and needs. I could see a pattern developing…

The example given was the AT&T Picture Phone, which originated in the 1960s. The company’s executives believed that a million units would be in use within 10 years of launch—but it was pulled off the market three years later due to a lack of consumer interest. Users found the equipment too bulky, its controls unfriendly, and its picture too small to enjoy viewing.

Blinded

Blinded by their own vision and the desire to make it succeed, the company ignored negative user feedback right from the first trials, and developed a product that failed to meet customer needs and wants. And then: they did the same thing again in the 1990s with a relaunch!

This made me really think hard about a product Abaco launched only yesterday—and whether it really addresses a customer need, or is just something we "want" to succeed.

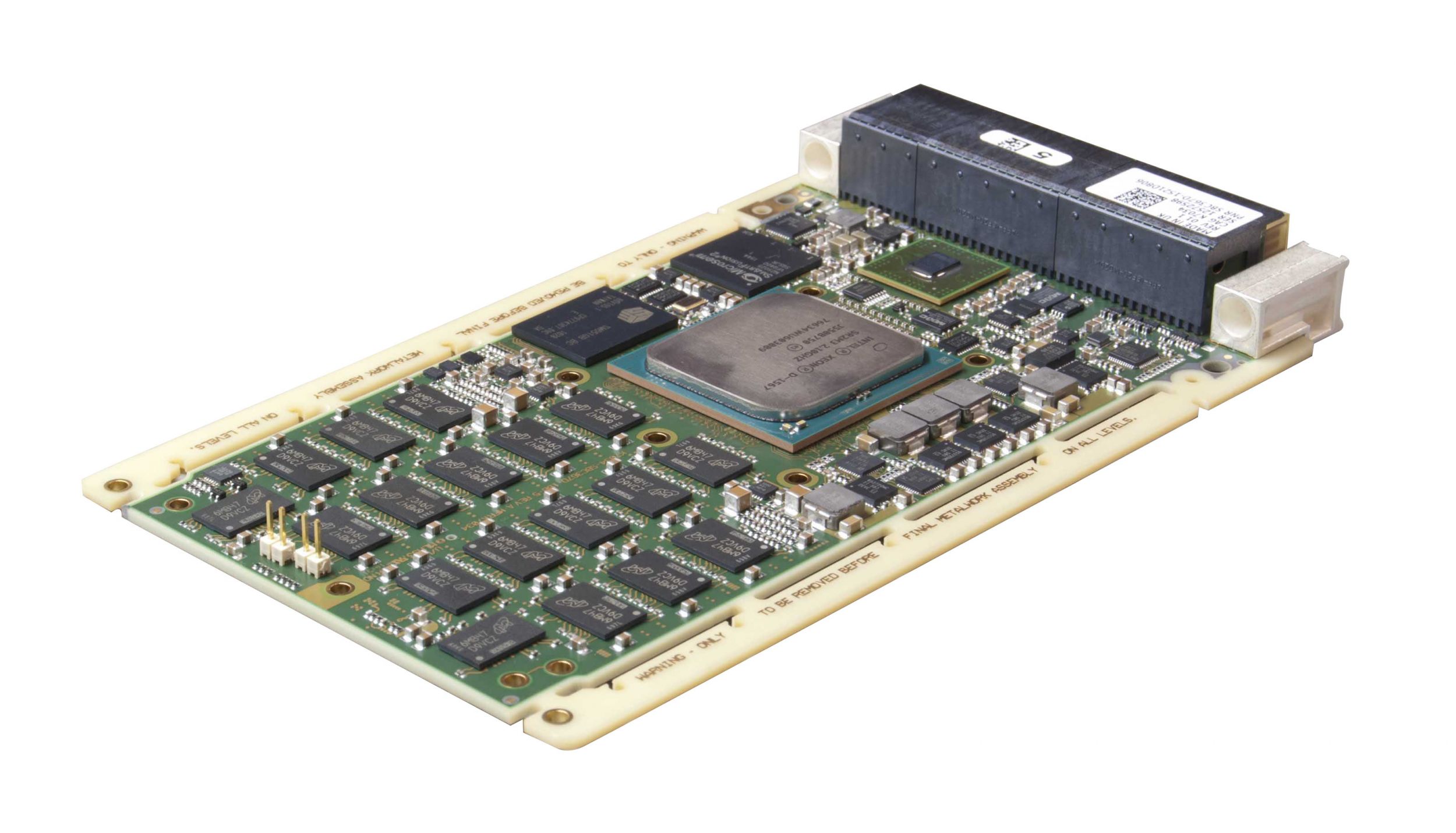

The new product in question is the SBC367D. It’s an OpenVPX single board computer. What makes it stand out is that it has a 40 Gigabit Ethernet data plane. In fact, so far as we can make out, the product is unique in the marketplace: we can’t find any other 3U OPenVPX SBCs anywhere that include 40 Gigabit Ethernet on the data plane.

Now: it’s great to be unique. But then, you start to wonder why no-one else has thought of this product. After all: that AT&T phone was unique too… I found myself asking the question: does the inclusion of a 40 Gigabit Ethernet data plane really satisfy a customer need, such that the product will be a success?

I think it does—and I think it will. Why? Because the SBC367D responds to a real customer need that our customers have been telling us about.

What they’ve told us is that, although PCI Express-based fabrics have served them well over the last decade, they see PCI Express as somewhat proprietary—and that’s never a good thing in our world of industry standards and open architectures.

Open, low latency, easy to use

They’ve told us that they’re looking towards Ethernet architectures because the Ethernet programming model is easily understood; that it scales easily from 1 Gigabit to 10 Gigabits to 40 Gigabits (and will, eventually, likely scale to 100 Gigabits) with minimal software impact; and that they prefer the Ethernet model when their application needs processing to be scaled, with multiple modules linked by a switch.

The bottom line, then, is that 40 Gigabit Ethernet in a 3U format single board computer allows extraordinarily high performance applications to be developed—in a computer that’s small, light weight and consumes minimal power. 40 Gigabit Ethernet is open; it’s low latency; and it’s easy to use. In the defense and aerospace market, where surprises and delays are the last thing our customers want, this counts for a lot.

Time will tell if our assessment is correct—but it seems pretty compelling for now. The SBC367D looks set to be a success, because it really responds to our customers’ requirements—and not just a small subset of those customers, but the majority of them.

I think I’ll sleep well tonight.